死刑犯的最后一餐Last Meals

In January 1985, Pizza Hut aired a commercial in South Carolina that featured a condemned prisoner ordering delivery for his last meal. Two weeks earlier, the state had carried out its first execution in twenty-two years, electrocuting a man named Joseph Carl Shaw. Shaw’s last-meal request had been pizza, although not from Pizza Hut. Complaints came quickly; the spot was pulled, and a company official claimed the ad was never intended to run in South Carolina.

It’s not hard to understand why Pizza Hut’s creative team thought the ad was a good idea. The last meal offers an irresistible blend of food, death, and crime that drives a commercial and voyeuristic cottage industry. Studiofeast, an invitation-only supper club in New York City, hosts an annual event based on the best responses to the question, “You’re about to die, what’s your last meal?” There are books and magazine articles and art projects that address, among other things, what celebrity chefs—like Mario Batali and Marcus Samuelsson—would have for their last meals, or what the famous and the infamous ate before dying. Newspapers reported that Saddam Hussein was offered but refused chicken, while Esquire published an article about the terminally ill Francois Mitterrand, the former French president, who had Marennes oysters, foie gras, and, the pièce de résistance, two ortolan songbirds. The bird is thought to represent the French soul and, because it’s protected, is illegal to consume.

While the number of yearly executions in the United States has generally declined since a high of ninety-eight in 1999, the website Dead Man Eating tracked and commented on last-meal requests of death-row inmates across the country during the first decade of the new millennium. One of the site’s last posts, in January 2010, was the request of Bobby Wayne Woods, who was executed in Texas for raping and killing an eleven-year-old girl: “Two chicken-fried steaks, two fried chicken breasts, three fried pork chops, two hamburgers with lettuce, tomato, onion, and salad dressing, four slices of bread, half a pound of fried potatoes with onion, half a pound of onion rings with ketchup, half a pan of chocolate cake with icing, and two pitchers of milk.”

There are also efforts to leverage the pop-culture spectacle of last meals to protest the death penalty. An Oregon artist has vowed to paint images of fifty last-meal requests of U.S. inmates on ceramic plates every year until the death penalty is outlawed. Amnesty International launched an anti-capital punishment campaign this past February that featured depictions of the last meals of prisoners who were later exonerated of their crimes.

No matter your stance on capital punishment, eating and dying are universal and densely symbolic human processes. Death eludes the living, and we are drawn to anything that offers the possibility of glimpsing the undiscovered country. If, as the French epicure Anthelme Brillat-Savarin suggested, we are what we eat, then a final meal would seem to be the ultimate self-expression. There is added titillation when that expression comes from the likes of Timothy McVeigh (two pints of mint-chocolate-chip ice cream) or Ted Bundy (who declined a special meal and was served steak, eggs, hash browns, toast, milk, coffee, juice, butter, and jelly). And when this combination of factors is set against America’s already fraught relationship with food, supersized or slow, and with weight and weight loss, it’s almost surprising that Pizza Hut didn’t have a winner on its hands.

The idea of a meal before an execution is compassionate or perverse, depending on your perspective, but it contains an inherently curious paradox: marking the end of a life with the stuff that sustains it seems at once laden with meaning and beside the point. As Barry Lee Fairchild, who was executed by the state of Arkansas in 1995, said in regard to his last meal, “It’s just like putting gas in a car that don’t have no motor.”

On January 14, 1772, in Frankfurt am Main, Susanna Margarethe Brandt prepared for her execution—she had killed her infant daughter—by sitting down to a sprawling feast with six local officials and judges. The ritual was known as the Hangman’s Meal. On the menu that day were “three pounds of fried sausages, ten pounds of beef, six pounds of baked carp, twelve pounds of larded roast veal, soup, cabbage, bread, a sweet, and eight and a half measures of 1748 wine.” Had she committed the crime in neighboring Bavaria, Brandt likely would have preceded the meal with a morning drink in her cell with the man who would later decapitate her with a sword. This shared aperitif was called St. John’s Blessing, after John the Baptist, who is said to have forgiven those who were about to behead him.

Brandt, who was twenty-five years old and is supposed to have inspired Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s character Gretchen in Faust, reportedly managed nothing more than a glass of water. Her companions in the repast fared little better.

The origins of the last-meal ritual aren’t settled. Although the earliest record of the death penalty is the Sumerian Code of Ur-Nammu in the twenty-second century BC, some scholars suggest the last meal may have begun in ancient Greece, and in Rome gladiators were fed a sumptuous last meal, the coena libera, the night before their date in the Colosseum. In eighteenth-century London, favored or better-off prisoners were allowed a party with food and drink and outside guests on the night before they were hanged. The next day, as the prisoner traveled the three miles from Newgate Prison to the gallows at Tyburn Fair, the procession would stop at a pub for the condemned’s customary “great bowl of ale to drink at their pleasure, as their last refreshment in life.” (England’s noble or high-born criminals, such as Anne Boleyn and the earl of Essex, were beheaded elsewhere, often at the Tower of London; Walter Raleigh reportedly took a last smoke from his tobacco pipe before he lost his head in Old Palace Yard at Westminster.) In the New World, the Aztecs feasted some of those who were tapped for ritual sacrifice, as part of a pre-execution deification ceremony that could last up to a year. Typically, these were warriors captured on the battlefield, and in some cases, after they were killed, their captor was given much of the body for use in tlacatlolli, a special stew of corn and human flesh that was served at a banquet with the captor’s family.

Today, most countries that use the death penalty as part of their criminal-justice systems offer some sort of last meal. Along with the United States, Japan and South Korea are the only industrialized democracies among the fifty-eight countries in the world that employ capital punishment, and in Japan, the condemned don’t know when they will be executed until the day arrives. In the 2005 documentary Last Supper, by the Swedish artists Mats Bigert and Lars Bergström, Sakae Menda, who spent thirty four years on death row in Japan, said inmates may request whatever they want; if no request is made, prison officials provide “cakes, cigarettes, and drink.” Duma Kumalo, who spent three years awaiting death in South Africa, told the filmmakers that he was served a whole deboned chicken and given seven rand—about six dollars—to purchase whatever else he wanted. “What we bought before execution, it was not things that we wanted to eat,” said Kumalo, who was spared for reasons he does not explain, just hours before he was to be killed. “Those were the things which we were going to leave behind with those who would remain. Because people were starving.”

In America, where the death rows—like the prisons generally—are largely filled with men from the lower rungs of the socio-economic ladder, last-meal requests are dominated by the country’s mass-market comfort foods: fries, soda, fried chicken, pie. Sprinkled in this mix is a lot of what social scientists call “status foods”—steak, lobster, shrimp—the kinds of foods that in popular culture conjure up the image of affluence. Every once in a while, though, a request harkens back to what, in the Judeo-Christian West, is the original last meal—the Last Supper, when Jesus Christ, foreseeing his death on the cross, dined one final time with his disciples. Jonathan Wayne Nobles, who was executed in Texas in 1998 for stabbing to death two young women, requested the Eucharist sacrament. Nobles had converted to Catholicism while incarcerated, becoming a lay member of the clergy, and made what was by all accounts a sincere and extended show of remorse while strapped to the gurney. He sang “Silent Night” as the chemicals were released into his veins.

The musician Steve Earle, whom Nobles asked to be among his witnesses at the execution, wrote of the experience in Tikkun magazine, “I do know that Jonathan Nobles changed profoundly while he was in prison. I know that the lives of other people with whom he came in contact changed as well, including mine. Our criminal justice system isn’t known for rehabilitation. I’m not sure that, as a society, we are even interested in that concept anymore. The problem is that most people who go to prison get out one day and walk among us. Given as many people as we lock up, we better learn to rehabilitate someone. I believe Jon might have been able to teach us how. Now we’ll never know.”

As of June of this year, governing bodies in the U.S. and its colonial predecessors had executed some 15,825 men and women since the first permanent European settlements were established. The majority of them, it seems, did not get a special last meal; the Newgate Prison parties didn’t make the crossing with William Bradford and John Carver aboard the Mayflower. There is no record of a last meal for George Kendall, believed to be the first Englishman executed in the New World, who was accused of spying for Spain and shot in Jamestown in 1608. (The nature of criminal justice around that time was such that Kendall would also have been shot—or hanged, beheaded, or burned at the stake—for stealing grapes.)

Scott Christianson, who has written extensively on the history of American prison culture, believes the standardized last meal probably emerged around the end of the nineteenth century or the beginning of the twentieth, with the rise of a modern administrative state. Messy and raucous public executions fell out of favor with the more refined sensibilities of the upper and middle classes, and ideas of man’s ability for moral improvement fueled opposition to the death penalty. Rehabilitation, rather than simply deterrence and retribution, became an important aim of criminal sanction. At the same time, though, there was still a strong fear of social disorder; the assertive state governments were eager to find better ways to keep the peace in a fledgling nation whose cities were growing, industrializing, and diversifying.

The answer, or so it seemed, was to replace the more communal sanctions of the colonial and early republic era—fines, banishment, floggings, labor—with long-term incarceration in state-run penitentiaries. Criminals would be isolated from society and purged of their deviant impulses. Executions, which had long been believed to have a scared-straight effect on the public, were now thought to inspire the very violence they were meant to deter. They moved to yards inside the prisons, where the witnesses were only a select few, usually prominent officials and merchants.

In addition to efficiency and decorum, Christianson writes, another “new aspect of this choreographed ritual of death entailed the release of detailed reports to the public that described,” among other things, “precisely what the condemned had requested as his or her last meal.” This gave the impression of a humane and dispassionate custodial government authority, but it also—intentionally or not—tapped into a bit of the old public fascination with executions, when a family might hop in the wagon, ride to the town square with a picnic basket in tow, and watch someone be “launched into eternity.”

The press, Christianson says, “ate it up.” This was the dawning of the penny press, when steam-driven printing presses spurred the development of a mass media in America. As executions vanished inside penitentiaries, newspapers discovered that the public was still eager for accounts of the proceedings. In 1835, for instance, readers of New York’s Sun and Herald newspapers learned that Manual Fernandez, among the first men at Bellevue Prison to be privately executed, enjoyed cigars and brandy on his last day, compliments of the warden.

Nearly two hundred years later, America is in the grips of a revolution in communication technology even more pervasive than the penny press. The death penalty was resurrected in 1976, after a ten-year-long, nationwide moratorium, and public interest in last meals was rekindled along with the debate over capital punishment. But, initially due to the rapidly merging news and entertainment industries, and eventually to the Internet, the debate was amplified and widened. In 1992, presidential candidate and Arkansas governor Bill Clinton was excoriated over his refusal to stop the execution in his state of Rickey Ray Rector, a man so mentally impaired that he asked to have the slice of pecan pie he had requested as part of his last meal saved so that he could eat it later—and that morbid fact became the story’s enduring detail. Before long, state corrections departments began posting last-meal requests on their websites. Texas, which was the first to do so, shut down its last-meals page in 2003, after it received complaints about the unseemly nature of the content.

The last meal as a cultural phenomenon grew even as capital punishment faded from public view, and in less than two centuries the country has gone from grisly public hangings, in which the prisoner was sometimes unintentionally decapitated or left to suffocate, to lethal injection, the most common form of execution in America today, in which death is “administered.” The condemned are often sedated before execution. They are generally not allowed to listen to music, lest it induce an emotional reaction. Last words are sometimes delivered in writing, rather than spoken; if they are spoken, it might be to prison personnel rather than the witnesses. The detachment is so complete that when scholar Robert Johnson, for his 1998 book Death Work, asked an execution-team officer what his job was, the officer replied: “the right leg.”

The public disappearance of state-sanctioned killing mirrors the broader segregation of death in an increasingly death-shy society. Dying, which had traditionally happened at home, surrounded by family and friends, began migrating into hospitals in the late nineteenth century, which is where most people die today.

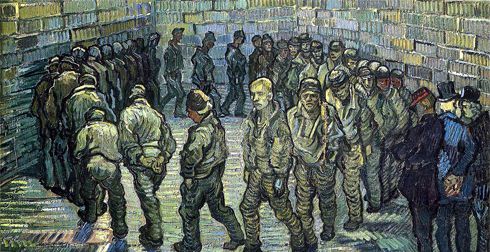

Rituals like the Hangman’s Meal and the Aztec sacrificial feasts were anything but detached. They were concerned with the spirituality of death—forgiveness, salvation, appeasing the gods, marking the transition from living to dead. Although prisoners may still pray with clergy, the execution process has been drained of its spiritual and emotional content. The last meal is an oddly symbolic and life-affirming ritual in the vigorously dehumanized environment of death row. In that sense, it’s hard to see the modern last meal in America as actually being about anything.

The last meal, though, is in some ways just an extreme example of the intimate relationship between food and death that is a part of end-of-life customs in nearly all societies. Christianity, after all, tethers the very idea of death to a culinary transgression: Eve and that damned apple. The ancient Egyptians painted images of food on the walls of tombs, so that if the deceased’s ancestors ever failed in their duty to make offerings, his soul would still be nourished and comforted. Native Americans observed a variety of ceremonies involving food when a member of a tribe died. The northeastern Hurons, for example, held a farewell feast to help them die bravely: the dying man was dressed in a burial robe, shared special foods with his family and friends, gave a speech, and led everyone in song.

Buddhists make food offerings to appease what the Japanese call gaki, or “hungry ghosts,” lest they return to haunt the living. Food is integral to Mexico’s Day of the Dead—which descended from Aztec festivals—when it is believed that departed souls return to earth. Graves are cleaned and repainted, and offerings of special foods—tamales and moles, sweet pan de muerto, skulls concocted of sugar (historically made of amaranth seeds), and liquor—are left for the dead to entice them to visit. And in America, food is brought to the family of the deceased after a funeral for comfort and convenience.

The Chinese, especially, use food to nourish and protect the dead—ancient Chinese even buried their dead with miniature models of stoves so they could prepare meals eternally—but they also, in return, hope to secure the dead’s blessings of prosperity, good health, and fertility upon the surviving family members.

When someone dies, one of the first tasks for the family is to help the deceased break from the community—to physically leave it—and begin the transformation from corpse to ancestor. Food is central to this process, sometimes as enticement and at other times as prod. In her book The Cult of the Dead in a Chinese Village, Emily Ahern describes how in one funerary ritual, a small bowl of cooked rice and a cooked chicken head are dumped on the ground. A dog is shown the food, and once the dog gets the chicken head in its mouth, it is “beaten with a long, whiplike plant until he dashes away in a frenzy…The dog represents the dead man, the chicken head the property” that belongs to his family. The idea is to chase away the dead man and make clear that “he has enjoyed his share of the property, so he should not come back and bother the living.”

What unites these customs is an emphasis on the needs of the living, not just the dead; so too with last meals before an execution. When Susanna Margarethe Brandt sat down to the Hangman’s Meal, she signaled that she was cooperating in her own death—that she forgave those who judged her and was reconciled to her fate. Whether she actually made those concessions or not is beside the point; the officials who rendered and carried out her sentence could fall asleep that night with a clear conscience.

With the American public now excluded from the execution process, much of the larger societal meaning of capital punishment, and last meals, has been lost. The community is no longer involved. In colonial America, executions were opportunities to reinforce publicly the Calvinist belief in the innate depravity of man, and also provided a little entertainment. People thronged to see how someone facing the final mystery of life behaved. On October 20, 1790, a crowd of thousands watched thirty-two-year-old Joseph Mountain, convicted of rape, be hanged on the green in New Haven, Connecticut. Would he confess and repent, as authorities hoped, or would he die “game,” denouncing the sentence?

Over the latter half of the twentieth century, with the notion of deterrence unproven and the promise of rehabilitation mostly forgotten, retribution and general incapacitation became the primary goals of the American criminal-justice system. This was in part due to the changing political climate. The neoconservative movement rose from the ashes of Barry Goldwater’s defeat in the presidential election of 1964, tapping into public concerns about the rising crime rate, a growing disaffection for social-welfare programs, and the unrest evident in the opposition to the Vietnam War as well as urban race riots. In response came the Rockefeller drug laws in New York, which launched over thirty years of tough-on-crime policies, and Ronald Reagan’s warning of the corrosive effects of the “welfare queen” who cheats the system. “Individual responsibility” became the defining doctrine for everything from America’s economic life to its crime-fighting strategies.

In 2007 the U.S. Supreme Court effectively upheld the retributive theory of capital punishment, and the idea of individual responsibility, when it ruled that a mentally ill prisoner could not be executed if he lacked a rational understanding of why the state was killing him, even if he was aware of the facts of the state’s case. As Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote for the court, “It might be said that capital punishment is imposed because it has the potential to make the offender recognize at last the gravity of his crime and to allow the community as a whole…to affirm its own judgment that the culpability of the prisoner is so serious that the ultimate penalty must be sought and imposed.”

In other words, the public’s need for retribution requires criminals that are somehow irredeemable monsters who still know right from wrong and freely chose to do horrible things; they are certainly not the profoundly disabled or the unfortunate byproducts of societal or familial breakdowns. But the image of the morally culpable public enemy is difficult to sustain in a criminal-justice system that strips away the prisoner’s individuality and free will, reducing him to something seemingly less than human. It’s hard for people to experience a satisfying sense of retribution when the state is, in effect, exterminating something aberrant and abstract, much as a surgeon removes a malignant tumor.

In the nineteenth century, when the American government was ending public executions, officials struggled with a similar dilemma. Historian Louis P. Masur explains how, without the official moralizing sermons that had accompanied public hangings, people “were free to construct their own interpretations rather than receive only an official one.” There was concern that executions carried out in private could foster doubts that justice was being done—that the prisoner was in fact guilty and that the proceedings had been fair. In short, whether the convict was indeed an irredeemable monster. In an effort to reclaim control of the narrative of capital punishment, the authorities saw the benefit of the new mass-circulation newspapers to feed the public information about executions. The press accounts made it seem that the public still had some sort of informal oversight of the killing done in its name.

Daniel LaChance, an assistant professor of history at Emory University, has argued that the rituals of a last meal—and of allowing last words—have persisted in this otherwise emotionally denuded process precisely because they restore enough of the condemned’s humanity to satisfy the public’s desire for the punishment to fit the crime, thereby helping to ensure continued support for the death penalty. As LaChance puts it, “The state, through the media, reinforces a retributive understanding of the individual as an agent who has acted freely in the world, unfettered by circumstance or social condition. And yet, through myriad other procedures designed to objectify, pacify, and manipulate the offender, the state signals its ability to maintain order and satisfy our retributive urges safely and humanely.” A win-win. The state, after all, has to distinguish the violence of its punishment from the violence it is punishing, and by allowing a last meal and a final statement, a level of dignity and compassion are extended to the condemned that he didn’t show his victims. The fact that the taxpayers are picking up the tab for these sometimes gluttonous requests only bolsters the public’s righteous indignation.

The final turn of the screw is that prisoners often don’t get what they ask for. It is the request, and not what is ultimately served—let alone what’s actually consumed, which is often little or nothing—that is released to the press and broadcast to the public. Most states have restrictions on what can be served and how much of it, a monetary limit, for instance, or based on what’s in the prison pantry on a given day.

So that filet mignon and lobster tail? It’s likely to end up being chopped meat and fish sticks, according to Brian Price, an inmate who cooked final meals for other prisoners in Texas for over a decade before he was paroled in 2003 (and subsequently wrote a book about the experience called Meals to Die For). The 2001 book Last Suppers: Famous Final Meals from Death Row, includes this teaser: “How’s this for a last meal: twenty-four tacos, two cheeseburgers, two whole onions, five jalapeño peppers, six enchiladas, six tostadas, one quart of milk, and one chocolate milkshake? That’s what David Castillo, convicted murderer, packed in the night before Texas shot him up with a lethal injection.”

What Castillo, who was executed in 1998 for stabbing a liquor-store clerk to death, actually got for his last meal was four hard-shell tacos, six enchiladas, two tostadas, two onions, five jalapeños, one quart of milk, and a chocolate milkshake. A hefty spread, but not quite the jaw-dropper he ordered.

And so it came to pass in Texas in 2011 that the state stopped offering special last meals, after Lawrence Russell Brewer ordered two chicken-fried steaks, one pound of barbecued meat, a triple-patty bacon cheeseburger, a meat-lover’s pizza, three fajitas, an omelet, a bowl of okra, one pint of Blue Bell Ice Cream, some peanut-butter fudge with crushed peanuts, and three root beers—and ended up not eating anything. This prompted an outraged state senator to threaten to outlaw the last meal if the department of corrections didn’t end the practice.

For his crackdown on taxpayer-funded excess, the senator surely earned hearty handshakes from his tough-on-crime constituents. But it is somehow fitting that the sham of the last meal, in Texas at least, which has executed hundreds more people over the last thirty years than any other state, was allowed to fade into history with its bundle of contradictions intact, buried by the calculated denunciation of a politician seizing on a way to stroke his base. Now in the Lone Star State, the men and women killed by the government get whatever is on the prison menu that day. Justice will be served.

1985年1月,必胜客在南卡罗来纳州投放了一个商业广告,讲述了一个死刑犯点必胜客的外卖作为最后一餐。两个星期之前,该州执行了它二十年来首例死刑,以电椅的方式处死了一个叫做约瑟夫·卡尔·肖的男子。肖最后一餐要求是披萨,虽然不是来自必胜客。很快就引起很多投诉,而且愈演愈烈,公司官员宣称,这个广告从没打算在南卡罗来纳州上上映的。

我们不难理解为什么必胜客的创意团队会认为这个广告是个很好的主意。最后一餐提供了一个令人难以抗拒的食物、死亡和犯罪的融合,这驱动了一个商业的、偷窥的家庭手工业。Studiofeast是纽约一个大型的邀请制的晚餐俱乐部,针对“如果你将要死去,什么将是你的最后一餐”的最佳回答每年举办晚会。有很多书、杂志和艺术项目中都有介绍,名厨师,如马里奥•巴塔利和马库斯·萨缪尔森 的最后一餐,或者著名人物或者声名狼藉的人最后一餐都吃了什么。新闻报告称萨达姆·侯赛因最后一餐有鸡肉,但是他拒绝了,而君子杂志出版的一篇文章报道,疾病晚期的密特朗总统,前法国总统,吃了马伦尼斯牡蛎,鹅肝,最主要的是,两只食米鸟黄莺。这种鸟被认为是法国的灵魂。它是受到保护,因此,食用它是非法的。

尽管与1999年98人的峰值比,每年在美国执行死刑的人数是在减少的,但是“死者的食谱”的网站对新千年的第一个十年里全国死囚的最后一餐进行了跟踪和评论。该网站最新的一个报道是,在2010年1越,鲍勃·韦恩·伍兹,因强奸并杀害一个11岁的女孩儿在德克萨斯被判死刑,的最后一餐请求:两个炸鸡排,两个煎鸡胸肉,三个煎猪排,两个生菜、西红柿、洋葱和沙拉酱汉堡包,四片面包,半磅的炸土豆和洋葱,半磅的洋葱圈加蕃茄酱,半锅糖霜的巧克力蛋糕,和两罐牛奶。

也有试图利用最后一餐的流行文化奇观来抗议死刑的努力。一位俄勒冈艺术家曾发誓每年在瓷砖上画五十份美国囚犯的最后一餐的需求,直到死刑被废除。国际特赦组织在今年二月发起的反死刑运动重点描述了几位后来被证明是清白的罪犯的最后一餐。

不管在死刑上你站在哪方的立场,饮食和死亡都是人类进程普遍又极端的象征。死亡让人逃避生活,我们被吸引到任何能为我们提供对未知世界一瞥的事物上。就像法国美食家安瑟米·布里勒特·萨瓦林说的那样,吃什么成就了我们是什么样的人,那么最后一餐可以看做是最后的自我表达。当这些表达来自像提摩太·麦克维(两品脱薄荷巧克力碎片冰激凌)或者泰迪·邦德(他拒绝了一顿特殊的晚餐,而要了牛排、鸡蛋、土豆煎饼、吐司、牛奶、咖啡、果汁、黄油和果冻)。当这些因素的组合与美国现有的令人担忧的食物、超重、减肥等关系比较时,必胜客没有成为赢家是非常令人惊讶的。

死刑前最后一餐的想法是富有同情心或者是有违常理,这取决你的看法,但是它确实包含一种内在的奇怪的矛盾:用一样事物标记生命的终结,维持它像是充满了意义但又像偏离了主题。就像巴利·李·菲儿查尔德——1995年在阿堪萨斯州被处以死刑,就他最后一餐说的,“就像给没有发动机的汽车注入汽油。”

1772年1月14日,在法兰克福,苏珊娜·玛格丽特·布兰德杀死自己还是婴儿的女儿,她等待执行死刑的准备是坐下来与当地六名官员和法官一起大吃了一顿。这个仪式被称为刽子手的一餐。那天的菜单是“三磅的煎香肠、十磅牛肉、六磅的烤鲫鱼、十二磅的猪油烤小牛肉、汤、卷心菜、面包、一份甜点和八杯半的1748年葡萄酒。”如果她是在附近的巴伐利亚犯罪的话,布兰德还可能会在牢房里,与等会用剑给她执行死刑的男人来个餐前酒。这个共享开胃酒被称为圣约翰的洗礼,在施洗约翰后,据说就会原谅那些被斩的人。

布兰德,25岁,据说是受到歌德的《浮士德》的启发,据报道平时的管理不超过一杯水。她的同伴的就餐条件已经稍微好了一点。

最后一餐这个仪式的起源至今未定。尽管最早的关于死刑的记录是公元前22世纪的乌尔纳姆的苏美尔代码,一些学者认为,最后一餐可能起源于古希腊,在罗马角斗士在他们在罗马圆形大剧场前一天晚上会被喂以丰盛的最后一餐。在18世纪的伦敦,有名或者有钱的犯人允许在绞刑前举办聚会宴请外面的客人。第二天,犯人要被绑在十字架上从纽盖特监狱走三公里到泰伯恩刑场,这个过程中还将在酒吧前停会儿,通常让犯人大碗喝酒享受他们在人世的最后的欢愉。(英格兰的贵族和贵族罪犯,安妮和埃塞克斯伯爵等人被斩首,通常是在伦敦塔,沃尔特·罗利据说在他在威斯敏斯特的旧皇宫广场前斩首时抽了最后一只烟)在新世界,阿兹特克人抽中一些人为仪式做出牺牲,作为为期一年的预执行神化仪式的一部分。通常,这些是在战争中捕获的战士,在一些情况下,在他们被杀后,他们的捕获者会被给予一些肉体用在特拉塔诺尼,这是玛雅人在祭祀后将尸体与玉米一起煮食,用在捕获者家庭宴会上的特殊食物。

现在很多还保留死刑的国家都会提供某种形式的最后一餐。美国、日本和韩国是58个工业化民主国家中为数不多的保留死刑的,在日本,犯人直到都不知道他们什么会被处死。2005年,由瑞典艺术家马特·比格特和拉尔斯·柏格隆制作的《最后的晚餐》,荣免田在日本的监狱里呆了34年,他说到,犯人可以提任何要求,如果没有提要求,狱卒会提供“蛋糕、香烟和饮料”。杜马·库马诺,在行刑前在南非的监狱呆了三年,他告诉电影制片人说,狱卒给他提供了一整只去骨鸡和七兰特——大约六美元,可以用这个钱购买他想要的东西。库马诺说,他们买的不是他们死前想吃的,而是他们想留给还活着的人的,因为这些人还在挨饿。库马诺在行刑前的几个小时被释放了,至于原因他并未解释。

在美国,死刑犯的监狱与普通的监狱差不多,都挤满了社会各个阶层的人,普遍的食物需求是:薯条、苏打水、炸鸡、派。这些需求中有少量的被社会学家称为“身份食物”——牛排、龙虾、虾制品,这些食物在流行文化中是富裕的象征。尽管每隔一段时间,都会对在信奉基督教和犹太教的西方,最后一餐的有个追溯的请求——当耶稣基督预见自己将钉死在十字架上,他与他的门徒们最后次了一顿饭。乔纳森·维恩·诺布尔斯于1998年在德克萨斯州因刺死两名年轻的女性而被判处死刑,他的最后一餐要求圣餐圣礼。诺布尔斯在监禁期间皈依了天主教,成为了一名世俗神职人员,据说他被绑在床上时,他表现出了真诚和无限悔恨。当化学药剂注入他血液时,他还唱着“平安夜”。

诺布尔斯音乐学家史蒂夫·厄尔来见证他死刑执行过程,厄尔在《修复》杂志上谈过这段经历,“我知道乔纳森·诺布尔斯在监狱你改变了很多。我知道与他交往的其他人的生活也在改变着,包括我自己的生活。这种修复是我们的司法系统所没有的。我也不确定,作为一个社会,我们是否还对那个概念有兴趣。问题是大多数进入监狱的人将来有天会出狱,与我们一起生活。考虑到我们关押了那么多人,我们最好还是要学会修复他们。我相信乔纳森已经教会我们如何去做。这些东西我们自己是永远无法知道的。”

截止今年6月,自从建立第一个欧洲永久居住地,美国及他的殖民地机构共处死了15,825名男男女女。这其中大部分人没有得到专门的最后一餐;纽盖特监狱的传统并没有随着威廉姆·布拉德福特和约翰·卡佛一起乘五月花号达到美国。乔治·肯德尔被认为是在新世界处死的第一个英国人,他被指控为西班牙的间谍,1608年在詹姆斯敦被枪决,目前没有关于他最后一餐的记录。(刑事处罚在那个时期的性质是肯德尔可能因为盗取情报信息被枪决,或者绞死或者在火刑柱上烧死。)

斯科特·克里斯蒂安森,他撰写了大量关于美国监狱文化历史的文章,他认为标准的最后一餐可能出现于19世纪末或者20世纪初,随着现代化管理国家的出现。随着上中层阶级情感细腻化,举止优雅的追求,混乱和喧嚣的公开处决方式逐渐没落,认为人的道德素养在提升的观点使得死刑的反对声更加响亮。修复,而不是简单的威慑和报应,称为司法判决的重要目的。与此同时,虽然也有人担心社会秩序的混乱,政府急需在一个羽翼未丰的国家找到一条平衡城市、工业和多样化发展的道路。

答案,或者看起来如此,是用国家管理的监狱的长期监禁替代更多的殖民和共和国早期的集体制裁——罚款、驱逐、鞭打、劳改。犯人与社会隔离开来,消除他们离经叛道的冲动。处决,长期以来被认为对公众具有直接威慑力,但是现在却被认为是刺激了它最初想要制止的暴力。他们转移到了监狱的室内,在那里见证者只是其中的一小部分,通常是主要的官员和商人。

除了效率和礼仪,克里斯蒂安森写到另一方面,“这种精心设计的死亡仪式的新的一面是需要向公众详细的描述的细节,”包括犯人要求的最后一餐。这使得政府行程呢过了一个人性化、公平的监管者形象的威信,但是它也——有意或者无意的——陷入传统的对老式公开处决的迷恋,一家人可能跳上马车,挎着篮子,涌入城市广场,观看别人“升天”。

克里斯蒂安森说,报社“解决了这个问题”。这也就是便士报的开端,当蒸汽印刷机刺激了美国大众传媒业的发展。当处决从监狱中消失后,报社发现大众仍然非常渴望知道过程的细节。1835年,例如,六月太阳先驱报的读者们获知费尔南德斯是第一个在贝尔维尤监狱私下处死的人,在他的最后一天,他尽情的享受了白兰地、雪茄和监狱长的恭维。

大约200年后,美国在通讯技术改革的控制方面比便士报社更加的普遍。1976年,在十年的全国暂停后,又恢复了死刑,随着对死刑的辩论,公众对最后一餐的兴趣又被重新点燃。但是,由于迅猛发展的报纸和娱乐产业,以及互联网的星期,这场讨论不断的扩大,再扩大。1992年,总统候选人,阿肯色州州长比尔·克林顿因为拒绝放弃对他所在州的尼基·雷校长的死刑而被大众责难,这名男子智力受损,他要求将他最后一餐的一片核桃派留下来以后吃——这个病态的事实也成为了故事讲述的细节。没过多久,美国劳教部门开始在网站上公布最后一餐的要求。德克萨斯州是第一个这么做的,它在2003年关闭了最后一餐的页面,此后,它收到很多关于其见不得人内容的抱怨。

当死刑从公众视野中消失后,最后一餐最为一种文化现象得到越来越多的关注,在两个世纪内,这个国家从恐怖的公开绞刑,有时候犯人也会被斩首或者窒息而亡,到致命注射,这是当今美国最常见的处死方式,在这些情况下,死亡都是可以管理的。犯人死前会服用镇静剂。他们不允许听音乐,以防产生情绪上的反应。最后的遗言多数是写在纸上的,而不是口述的。如果他们是口述的,他可能是对着监狱的工作人员而不是死刑的见证者。这个团队是非常完整的,当学者罗伯特·约翰逊1998年写他的《死亡工作》时问一个死刑执行团队的官员,他负责的工作是什么时,这个官员回答,“右腿”。

国家认可的杀戮从大众视野里消失反映了死亡在一个对死亡的胆怯与日俱增的社会中越来越明显的隔离。死亡,传统上都发生在家里,被亲戚朋友围着,在19世纪后期开始向医院转移,现在大多数人都在医院里死去。

刽子手的一餐或者阿兹泰克人祭祀盛宴的仪式其实都是分离。他们关心的是死亡的意义——宽恕、救赎、安抚众神,标志着从生存到死亡的转变。尽管犯人可能仍然向神职人员祈祷,但是他们死刑的过程已经没有精神和灵魂的内容。最后一餐是在非人性的监牢环境下的奇怪的符号和生命仪式。从那种意义来说,很难说美国现代的最后一餐到底是什么?

虽然从某些角度说最后一餐是食物与死亡亲密关系的一个极端例子,它几乎是所有社会里临终习俗的一部分。毕竟,基督教将死亡与厨房的侵犯联系在一起:夏娃和那个该死的苹果。古埃及人在坟墓的墙壁上画食物,所以,即使已故的祖先没有尽到上供的责任,他的灵魂也能得到安息。当有部落成员去死时,美国土著会看到很多与食物有关的仪式。比如,东北部的休伦湖区,会举行送别盛宴帮助他们勇敢的离开:将死之人穿着葬礼的长袍,与他们的家人和朋友分享特别的食物,发表演讲,领导大家一起歌唱。

佛教徒会向“恶鬼”提供食物,为了让他们回来妨碍生活。食物墨西哥亡魂日不可或缺的东西,亡魂日是从阿兹泰克流传下来的节日,它被认为是死去的亡魂返回地球的例子。坟墓得到清理和粉刷,还会提供很多特别的食物——玉米粉蒸鼹鼠肉、甜甜的亡灵面包、头骨炮制的糖(历史上是用苋属植物种子)、酒——留给死人吸引他们的来访。在美国,为了方便和舒适,也会给举行葬礼的人家送吃的。

在中国,尤其会用食物来滋养和保护死者——古代中国人甚至将所谓的炉灶模型与死人埋在一起,这样它们就永远都能做饭了——作为回报,他们希望死者能保佑活着的家庭成员健康长寿、富裕安康。

当有人去世的时候,这个家庭的第一项任务就是帮助死者从社区中剥离开——从身体上离开他——然后开始从尸体到祖先的转变。在这个过程中,食物是中心,有时候像是诱惑,有的时候又像是棍棒。在艾米丽·阿埃伦的《中国村落的死亡崇拜》一书中,她描述了一个葬礼仪式上,一小碗米饭和一只煮熟的鸡头被倒在地上,出现了一只狗,它把鸡头叼在嘴里,猛然“被人用长棍鞭打,直到它落荒而逃......这只狗代表了死者,这只鸡头代表了属于他们家族的财富。”其仪式是为了赶走死者,使其明白“他已经享受了他那份财富了,所以他不要回来了,不要来打扰生者了。”

将这些习俗联系在一起的是对生者的重视,而不是对死者,处死前的最后一餐也是这样。当苏珊娜·玛格丽特·布兰德坐下来享受刽子手一餐时,她就像是表示,她在处理自己的死亡——她原谅了那些判决她并决定她命运的人。不管她是否做了这些让步都不是重点,但是那些对她做出判决的官员能安心睡觉,问心无愧了。

现在美国公众在抗议死刑,死刑和最后一餐的社会意义已经消逝了。社区不再参与。在美国的殖民地,死刑是公开加强加尔文信徒在人本性堕落的信仰的机会,但是也提供了一些娱乐。人们蜂拥而来看一个人在面对人生最后的谜题时是如何表现的。1790年10月20号,数千人围观了32岁的约瑟夫·芒廷在康涅狄格州,纽黑文的绿地上被绞死,他被指控为强奸罪。他会想当局希望的那样认罪和忏悔吗,或者他像“游戏”样死去,谴责这个判决?

20世纪下半页,威慑的概念得不到证实,修复的承诺几乎被忘记,报复和使其丧失能力成为美国司法系统主要的目标。这也部分是因为处于变化状态的政治气候。新保守主义运动从1964年,巴利·戈登华特失败的总统竞选中死灰复燃,使公众对上升的犯罪率,糟糕的社会福利计划,明显的反越战情绪和种族骚乱感到担忧。作为回应,纽约颁布了洛克菲勒禁毒法案。该法案是过去30年中对犯罪最严苛的政策,罗纳德·里根警告欺骗福利系统的“福利女王”的腐蚀效应。“个人责任”成为从美国经济生活到它的抵抗犯罪战略的定义原则。

2007年,美国最高法院高效的提出死刑的惩罚理论和个人责任的观点,当它处理的对象是个心智不健全的人时,不能处以死刑,因为他不能理解为什么国家要杀他,即使他知道这个案情的事实。大法官安东尼·肯尼迪向法庭写到,“这可以说,死刑是可以实施的,因为它有使反抗者意识到自己罪行的严重性,使社区团结起来的潜能——要肯定自己对犯人严重罪行的判断,这样的话最后的惩罚才能找到并实施。

换句话说,公众对惩罚的需要要求有些不能原谅的怪物的犯人有辨明是非的能力,并且自由的选择做恐怖的事情。他们肯定不是严重残疾或者社会、家庭破碎的不幸的副产品。但是这种道德上有罪的社会公敌的形象在去除犯人个性和自由意志,使他失去人的权利和自由的司法系统中是难以持续的。当国际去除异常和抽象事物时就像外科医生去除脑内肿瘤时,这很难让人们体验到满意的惩罚感。

在19世纪,当美国政府停止公开处死,官员遇到类似的困境。历史学家路易斯·P·马祖尔解释道,没有官方的关于公开绞刑的说教布道,人们是怎么“自由的构建他们自己的诠释而不是只接受官方那一个说法”。也曾有担忧,私下执行死刑会对公正性产生怀疑。简而言之,不管罪犯是否确实是不可饶恕的怪兽。在收回死刑控制权的努力中,当局看到了新型大量发行的报纸对于公众获取行刑信息的优势。记者的描述使得大众对这种有各种名目的杀戮有了某种形式的监管。

丹尼尔·罗钱斯是埃默里大学的一名历史学助理教授,他争辩道,最后一餐——和最后遗言——的仪式,恰恰是坚持这本来剥夺情绪化的过程,因为他们使得犯人恢复了一些人性来满足公众们给予罪犯相应惩罚的需求,因此有助于死刑一直得到支持。就像罗钱斯提出的,“国家通过媒体加强了个体作为世界上独立活动主体对惩罚的理解,不受环境或者社会状况的影响。然而通过无数其他的用来拒绝、安抚和操纵罪犯的程序,国家显示了它在维护秩序、安全而人性的满足了我们惩罚犯罪的需求的能力。”这是种双赢的战略。毕竟,国家必须要将自己用来惩罚罪犯的暴力与它想要惩罚的暴力区分开来,通过最后一餐和最后的遗言,将认同和同情延伸到那些没有受害者的罪犯们。事实上纳税人有时候在为支持公众公义的愤慨饕餮行为买单。

这个螺旋的最后一次转变是犯人通常得不到他想要的。这只是要求,而不是他们最后得到的——更不用说实际上他们吃的,通常只有一点点或者什么都没有——这被记者向大众报道了出来。大多数国家都对提供什么,提供多少有着严格控制,有个消费限度,比如,基于某天监狱厨房有什么。

所以菲力牛排和龙虾尾?根据布莱恩·普莱斯的介绍,在这里可能是切碎的肉和鱼排,他在2003年假释前曾在德克萨斯州为其他罪犯烹饪最后一餐超过十年(之后,他出了一本书《死前一餐》介绍这段经历)。在2001年出版的《最后的晚餐:死刑囚牢中有名的最后一餐》里包括这样的玩笑:这怎么能成为最后的一餐:24个玉米饼、两份奶酪、两个完整的洋葱、五个墨西哥胡椒、六个辣酱玉米馅饼、六个炸玉米粉圆饼、一品脱的牛奶和一杯巧克力奶昔?这是犯了谋杀罪的大卫·卡斯迪诺夫教授在德克萨斯州注射死亡前一晚上打包好的东西。“

卡斯迪诺夫教授在1998年因刺死一个酒吧店员而被判处死刑,实际上他的最后一餐是四个硬壳玉米饼,六个辣酱玉米馅饼,两个炸玉米粉圆饼,两个洋葱,五个墨西哥胡椒,一品脱咖啡和一杯巧克力奶昔。经过大量的传播,说的都不是他当时点的那令人大吃一惊的东西了。

到了2011年,德克萨斯州停止供应最后一餐,在罗伦斯·罗素·布鲁尔点了两个炸鸡排、一磅烤肉、一份培根奶酪三明治、一份肉食者披萨、三份春饼、一份煎蛋卷、一碗秋葵、一份蓝钟冰激凌、一些花生酱带碎花生软糖、三杯啤酒——但最后他什么也没有吃。这使得议员非常生气,他们威胁到如果劳教部门不停止这项活动就将最后一餐视为非法的。

对纳税人基金的打压是多余的,议员肯定从他对犯罪的强硬态度中收获很多支持。但是这也与虚假的最后一餐有点相称,至少是在德克萨斯州,它在过去三十年里它比其他州多处死了几百人,最后一餐与它的矛盾结合体一起消逝在历史中,被政客抓住它的根基不断的谴责所掩埋。现在在孤星州,监狱里犯人在被处死时能得到的只是当天监狱菜单上说供应的东西。正义将得到伸张。